Falklands War hero reveals: “It has been 40 years and I can still smell death” in exclusive interview with Ustreme

“When the sun rose and the ground warmed up after a freezing night there was a mist that hovered and you could see the devastation clearly for the first time. The dead of the enemy, the dead of your friends, discarded equipment, empty shells, the wounded screaming. The smell of death. It was like a scene straight from hell.”

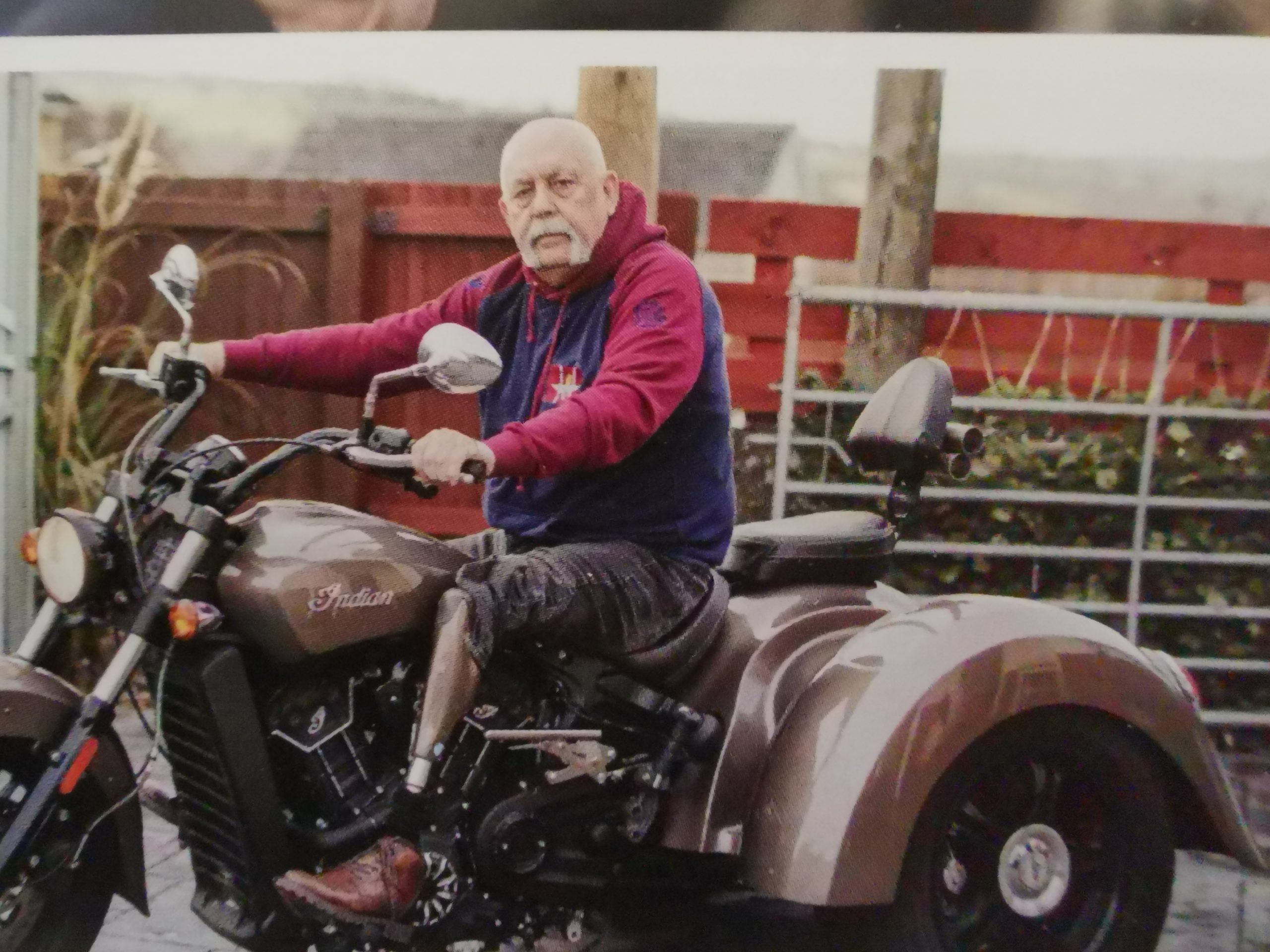

The devastating scene that faced Paratrooper Denzil Connick after a violent and bloody 12-hour battle on Mount Longdon, in the Falkland Islands, is a real-life horror story he continues to replay in his mind almost daily.

The 40 years since the conflict have done little to diminish the mental scars that serve as a constant reminder of the brutality of war. Much like the prosthetic leg he has worn since having his own blown off by a mortar bomb.

“I will never forget that scene” he says. “There aren’t many days that go by that I don’t think about it. It will never, ever go away.”

Denzil was a member of 3 Para, deployed to liberate the people of the islands after the Argentine invasion in 1982.

Having signed up to The Parachute Regiment’s Junior Parachute Company in 1972 and then joining 3 Para in 1974, he had much pride and love for the career that had taken him around the world, including Canada, Malaysia, Sudan and Europe.

His oath to Queen and Country had also seen him deployed for three harrowing tours of Northern Ireland, where ‘awful incidents happened daily and where I saw some of the worst scenes I’d ever witnessed’.

But his own personal experiences in Northern Ireland paled into insignificance compared to the Falklands War for Denzil, who suffered catastrophic and life-changing injuries in the conflict.

As a member of The Parachute Regiment, with its ‘Utrinque Paratus’ motto, Denzil was ready for anything. He was part of a unit that was on standby to be deployed to any conflict zone within 24 hours – and in 1982, Northern Ireland and the Middle East seemed the most likely locations for trouble.

But what he had not prepared for at that moment was for Argentina to invade the British Overseas Territory of the Falkland Islands.

“We are not politicians, we are soldiers that do as we are told,” says Denzil, from Blackwood, near Caerphilly. “The thought of ‘what am I doing?’ does cross your mind sometimes. But even if you don’t agree, you will always do as you are told. That is the allegiance you have taken and that is the job.

“The Falklands War just came out of nowhere. None of us were prepared for it to happen. Most of us wouldn’t have even been able to tell you where the Falklands Islands even are, at the time.”

Denzil was among the Paratroopers and 3 Commando Brigade of the Royal Marines who sailed to the Falkland Islands on the ocean cruise liner SS Canberra – which came complete with swimming pools hastily covered with steel plates to transform them into makeshift helicopter pads – and their ‘D-Day’ came when they arrived at Port San Carlos on May 21st 1982.

“We did a lot of our preparations on the journey there but we honestly still didn’t know a lot about what was going on over there. It was difficult to know what we were getting into.

“On the way over, we still believed that the diplomats would sort it out and we’d be turned around and sent home.”

That was until the Tannoy message that bellowed over their ship changed everything.

Nuclear-powered Hunter Killer submarine HMS Conqueror had sunk the Argentinian General Belgrano. Britain was committed to the fight.

“As soon as that message broke, we knew there was no going back,” says Denzil. “We knew we were going to war.”

The men who piled off SS Canberra on to the shore had been warned that they would be faced with an enemy waiting for their arrival.

“We were expecting casualties straight away,” says Denzil. “We were told there was at least a company’s strength waiting for us but the attack never came. The enemy had deserted the settlement and we went ashore unopposed, to great relief.

“You walk into danger knowing you may die. You can’t dwell on that. It is the deal you accept. But don’t think I wasn’t terrified. I was terrified most of the time.”

Soon after getting on to shore, the air attacks started. Denzil and his fellow Paratroopers and Royal Marine Commandos could only watch on helplessly as bombs rained down on the British ships anchored in the bay.

“We had a grandstand view. We could do nothing, just watch, as they attacked our Brothers in Arms.

“It was sad to see. It brings out this incredible frustration in you. Some of the men were shooting 9mm pistols at the jets just so they felt they were doing something.

“All that did though was to make us so much more determined. You felt we needed payback.”

Their anger was compounded further when they got word of the dozens of dead and wounded from Goose Green – the first and longest battle of the war, fought by 2 Para on May 28th and 29th 1982.

“Once we heard of the casualties of our 2 Para brothers at Goose Green, it drove us. We were almost looking forward to the punch up.

“There is nothing more motivating than hearing someone has hurt your friends and it geared us up for the fight. We were angry. It was a key moment when it came to our mentality.”

The 10-week war – which would ultimately claim the lives of more than 900 military personnel and civilians on both sides – was coming to an end when, on June 11th 1982, Denzil and his fellow Paratroopers would be engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the conflict at the Battle of Mount Longdon.

“We were preparing for a silent assault”, he says. “We would sneak up in the dark with our bayonets and surprise them in their sleeping bags.

“We formed at the start line and the order was whispered to fix our bayonets. Then the order was whispered to advance. We had to whisper because we were close to the enemy and didn’t want to alert them.

“But one of the members of the lead platoon then stepped on a land mine. Unbeknown to us we were in a minefield but the ground was frozen solid and so they hadn’t detonated.

“This one did, though, and it gave the enemy vital moments to get out of their sacks and start shooting at us.”

What followed was 12 hours of bloodshed and horror.

“It was just absolute bedlam,” he says. “It was dark. There were tracers and grenades going off. There were men screaming, wounded, dying.

“You would have the enemy in front of you and behind you. There was so much going on and people were losing contact with each other and having to fight in pairs.

“Some of the fighting was medieval. We were using bayonets to save our ammunition. The combat lasted 12 hours. It’s unbelievable really. It was just chaos.”

Denzil – at the time a 25-year-old radio operator co-ordinating the Support Company Milan anti-tank missile team and the sustained fire general purpose machine gun teams – says one of the most terrifying and heartbreaking moments of the battle was when the three-strong Milan team behind him were hit with a recoilless rifle round and killed.

With tears in his eyes, he says: “I can still hear the sound it made as it came towards us. It was like being hit by a train.

“It was horrific. It killed the entire team. It was appalling and that moment has had a profound effect on me.”

The scene of ‘hell’ that awaited the survivors of the 12-hour fight is a memory that is emblazoned in his mind for all time.

And, a day later, his life changed forever.

“They started shelling us,” he says. “It’s just a complete lottery out there. The only way to survive is digging down and getting under cover but we had to move around.

“I was hit by a mortar shell which tore my left leg completely off and shredded my other leg.

“It’s a weird sensation. I was lying on my stomach and could feel almost a burning feeling – but it wasn’t severe pain as such. I could see smoke coming from my cuffs. I could see my helmet rolling down the hill and thought, ‘Oh bloody hell, I’m going to have to go and get that’.

“Then I rolled on to my back and sat up. I saw my injuries for the first time and I screamed for Wales.

“The shelling was continuing around us, it was still chaos, and the men ran over to me. I was taken to the regimental aid post for life-saving First Aid. Those men risked their lives to save mine.”

Denzil was one of three critically injured soldiers from the hit – and he had been triaged as the most likely to die. But the other two men succumbed to their wounds next to him, and he was flown to a field hospital at Fitzroy.

On arrival, he momentarily died due to a heart attack caused by his severe loss of blood but was resuscitated and the next day was sent to the hospital ship, SS Uganda, where he underwent further surgical operations and his recovery began.

“I stayed conscious right up until the moment I ‘died’,” he says. “You just know when you don’t have long left in the world and I could feel myself getting weaker. I knew I’d have to stay awake else I wouldn’t have made it.

“It doesn’t actually feel scary at that moment, it is almost peaceful. But I thought of my family and how much they would be hurt and I had a grim determination to keep going.”

Denzil was conscious when he got news the very next day that the Argentinians had surrendered and the war was over.

“Some people in my position may think, ‘if only they had done that a day earlier’…but I consider myself one of the lucky ones. I survived.

“I was able to come home to my family and have a wonderful life, getting married and having children.

“We all played our part. It was a huge joint military operation, the likes of which had not been seen since the Normandy landings in 1944. We had friends in the wings but Britain was on her own, and we all have a bond with each other that will never be broken. When we get together now, we don’t dwell on the awful things we saw, we can laugh about the times we had while we were serving and talk about the brothers we lost.

“I say that men don’t really ever die if they are always remembered, and that’s what we always do.

“I still think us getting involved was the right decision. Those people had done nothing wrong, they were invaded and they needed our help.

“It sent out a message to the world: We are British. Don’t mess with us.”

*WATCH Denzil interviewing other Falklands heroes, including Brigadier Julian Thompson, for Ustreme’s new Pull Up A Sandbag series. Streaming exclusively for members at Ustreme.com from June 1.